703

1

ADOPTED

AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION

NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF COMMISSIONERS ON UNIFORM STATE LAWS

SECTION OF DISPUTE RESOLUTION

SECTION OF STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT LAW

REPORT TO THE HOUSE OF DELEGATES

RESOLUTION

RESOLVED, that the American Bar Association approves the Uniform Collaborative Law 1

Rules and Uniform Collaborative Law Act, promulgated by the National Conference of 2

Commissioners on Uniform State Laws in 2010, as appropriate Rules or an appropriate 3

Act for those states desiring to adopt the specific substantive law suggested therein. 4

703

1

REPORT

Collaborative law is a “voluntary, contractually based alternative dispute resolution

process” whereby parties use collaborative attorneys to engage in negotiation to

resolve their dispute and refrain from any litigation activity during the course of the

representation.

1

The parties agree in advance through their participation agreement,

the contract governing the process, that the collaborative attorneys would be

disqualified from representing the parties in court if the negotiations are unsuccessful.

2

Collaborative practice emerged in the late 1990s. In 2010, the National Conference of

Commissioners on Uniform State Laws (“NCCUSL”) finalized the Uniform

Collaborative Law Rules and Uniform Collaborative Law Act (“UCLA”) to govern the

process. The drafters recognized that states may choose to adopt the act through

legislation, similar to the adoption of laws governing other ADR processes, or as rules,

similar to the adoption of rules governing lawyer conduct, or as a combination of both

statutes and rules.

3

At the ABA Annual Meeting in 2011, the House of Delegates declined to adopt the

UCLA by a vote of 298 to 154.

4

Two primary concerns arose at the time. First, some

participants questioned the ethics of a negotiation-only practice as a limited-scope

representation. Second, others expressed concerns about the form of the UCLA as

legislation, as opposed to being limited to court rules.

More than a decade has passed since the House of Delegates considered issues

involving collaborative law, and the above concerns have been addressed. An

overwhelming number of ethics opinions support the UCLA approach to collaborative

practice. Further, each of the twenty-three jurisdictions that has adopted the UCLA has

carefully considered the separation of powers issues and arrived at solutions that meet

each jurisdiction’s need. Some jurisdictions adopted the law as a court rule, others as

statute, and other jurisdictions, like Illinois and Alabama , used a hybrid approach and

enacted provisions in statute and court rule.

This report proceeds in three parts. Part I provides an overview of the UCLA. Part II

identifies the states that have adopted the UCLA, as well as the form of the UCLA

adopted. Part III describes the resolution of the ethical questions regarding

collaborative practice.

I. OVERVIEW

In its Report to Resolution 110B of 2011 NCCUSL provided a concise overview of the

UCLA. This summary is reproduced from that report as a refresher on the terms of the

Uniform Collaborative Law Act and Rules:

1

Uniform Collaborative Law Act, Prefatory Note at 1 (2010).

2

Id.

3

Prefatory Note, at 20-21.

4

Resolution 110B (August 2011).

703

2

Rule/section 1 sets forth the title: Uniform Collaborative Law Rules/Act.

Rule/section 2 sets forth definitions of terms used in the Rules/Act.

[amended in 2010 to allow states to limit the application of the Rules/Act

to family law disputes].

Rule/section 3 makes the Rules/Act applicable to a collaborative law

participation agreement signed after the effective date of the Rules/Act

and provides that a tribunal cannot order a party to participate in the

collaborative law process over that party’s objection.

Rule/section 4 establishes minimum requirements for a collaborative

law participation agreement, which is the agreement that parties sign to

initiate the collaborative law process. The agreement must be in writing,

state the parties’ intention to resolve the matter (issue for resolution)

through collaborative law, contain a description of the matter and identify

and confirm engagement of the collaborative lawyers. The Rule/section

further provides that the parties may include other provisions not

inconsistent with the Rules/Act.

Rule/section 5 specifies when and how the collaborative law process

begins and how the process is concluded. Rule/section 5 highlights that

the collaborative process is voluntary – a tribunal may not order a party

to participate in a collaborative law process over that party’s objection.

The process begins when parties sign a participation agreement and any

party may unilaterally terminate the process at any time without

specifying a reason. The collaborative process is concluded by a

negotiated, signed agreement resolving all or part of the matter, or

termination of the process.

Several actions will terminate the process, such as a party giving notice

that the process is terminated, , a party requesting a hearing in an

adjudicatory proceeding without the agreement of all parties, or the

discharge or withdrawal of a collaborative lawyer. The Rule/section

further provides that under certain conditions the collaborative process

may continue with a successor collaborative lawyer in the event of the

withdrawal or discharge of a collaborative lawyer. The parties’

participation agreement may provide additional methods of terminating

the process.

Rule/section 6 provides for an automatic application for stay of

proceedings before a tribunal (court, arbitrator, legislative body,

administrative agency, or other body acting in an adjudicative capacity)

once the parties file a notice of collaborative law process with the tribunal.

A tribunal may require status reports while the proceeding is stayed;

703

3

however, the scope of the information that can be requested is limited to

insure the confidentiality of the collaborative law process.

Rule/section 7 creates an exception to the stay of proceedings by

authorizing a tribunal to issue emergency orders to protect the health,

safety, welfare or interests of a party or family or household member; or

to protect financial or other interests of a party in any critical area in any

civil dispute.

Rule/section 8 authorizes a tribunal to approve an agreement resulting

from a collaborative law process.

Rule/section 9 sets forth a core element and the fundamental defining

characteristic of the collaborative law process: should the collaborative

law process terminate without the matter being settled, the collaborative

lawyer and lawyers in a law firm with which the collaborative lawyer is

associated are disqualified from representing a party in a proceeding

before a tribunal in the collaborative matter, except to seek emergency

orders (Rule/section 7) or to approve an agreement resulting from the

collaborative law process (Rule/section 8). The disqualification

requirement is further modified regarding collaborative lawyers

representing low-income parties (see Rule/section 10) and governmental

entities as parties (see Rule/section 11).

Rule/section 10 creates an exception to the disqualification of lawyers

representing low-income parties in a legal aid office, a law school clinic

or a law firm providing free legal services to low-income parties. If the

process terminates without settlement, a lawyer in the organization or

law firm with which the collaborative lawyer is associated may represent

the low-income party in an adjudicatory proceeding involving the matter

in the collaborative law process if: the party has an annual income that

qualifies the party for free legal representation; the participation

agreement so provides; and the collaborative lawyer is appropriately

isolated from any participation in the adjudicatory proceeding.

Rule/section 11 creates a similar exception to the disqualification

requirement for lawyers representing a party that is a government or

governmental subdivision, agency or instrumentality.

Rule/section 12 sets forth another core element of collaborative law:

parties in the process must, upon request of a party, make timely, full,

candid, and informal disclosure of information substantially related to the

collaborative matter without formal discovery, and promptly update

information that has materially changed. Parties are free to define the

scope of disclosure in the collaborative process, so long as they do not

violate another law, such as an open records act.

703

4

Rule/section 13 acknowledges that standards of professional

responsibility of lawyers and abuse reporting obligations of lawyers and

all licensed professionals are not changed by their participation in the

collaborative law process.

Rule/section 14 deals with appropriateness of the collaborative law

process. Prior to the parties signing a participation agreement, a

collaborative lawyer is required to discuss with a prospective client

factors which the collaborative lawyer reasonably believes relate to the

appropriateness of the prospective client’s matter for the collaborative

process, and provide sufficient information for a prospective client to

make an informed decision about the material benefits and risks of the

process as compared to the material benefits and risks of other

reasonably available processes, such as litigation, arbitration, mediation

or expert evaluation. Further, a prospective party must be informed of the

events that will terminate the process and the effect of the disqualification

requirement.

Rule/section 15 obligates a collaborative lawyer to make a reasonable

effort to determine if a prospective client has a history of a coercive or

violent relationship with another prospective party, and if such

circumstances exist, establishes criteria for beginning and continuing the

process and providing safeguards.

Rule/section 16 provides that oral and written communications

developed in the collaborative process are confidential to the extent

agreed by the parties or as provided by state law other than the

Rules/Act.

Rule/section 17 creates a broad privilege prohibiting disclosure of

communications developed in the process in legal proceedings. The

provisions are similar to those in the Uniform Mediation Act and apply to

party and non-party participants in the process.

Rules/sections 18 and 19 provide for the possibility of waiver of

privilege by all parties, and certain exceptions to the privilege based on

important countervailing public policies such as preventing threats to

commit bodily harm or a crime, abuse or neglect of a child or adult, or

information available under an open records act, or to prove or disprove

professional misconduct or malpractice. Parties may agree that all or part

of the process is not privileged.

Rule/section 20 permits enforcement of an agreement made in a

collaborative process, even if (i) that agreement fails to meet the

mandatory requirement for a participation agreement (Rule/section 4),

703

5

or (ii) a collaborative lawyer involved in the process has not fully

complied with the disclosure requirements (Rule/section 14) or made a

reasonable inquiry whether a prospective party has a history of a violent

or coercive relationship with another prospective party (Rule/section

15))when the interests of justice so require. . The discretion accorded

to a tribunal may be exercised if the tribunal finds that the parties

intended to enter into a participation agreement, and reasonably

believed that they were participating in the collaborative process.

Section 21 recognizes one of the underpinnings of all uniform acts - the

desire to promote uniformity in applying and construing the Act among

states that adopt it. [no equivalent rule provision]

Section 22 provides that the Act may modify, limit or supersede certain

provisions of the Federal Electronic Signatures in Global and National

Commerce Act. [no equivalent rule provision]

Section 23 is a severability clause [no equivalent rule provision]; and

Rule/Section 24 establishes an effective date for the Rules/Act.

The UCLA makes no recommendation as to whether the law should be adopted as a

law, rule, or in hybrid form.

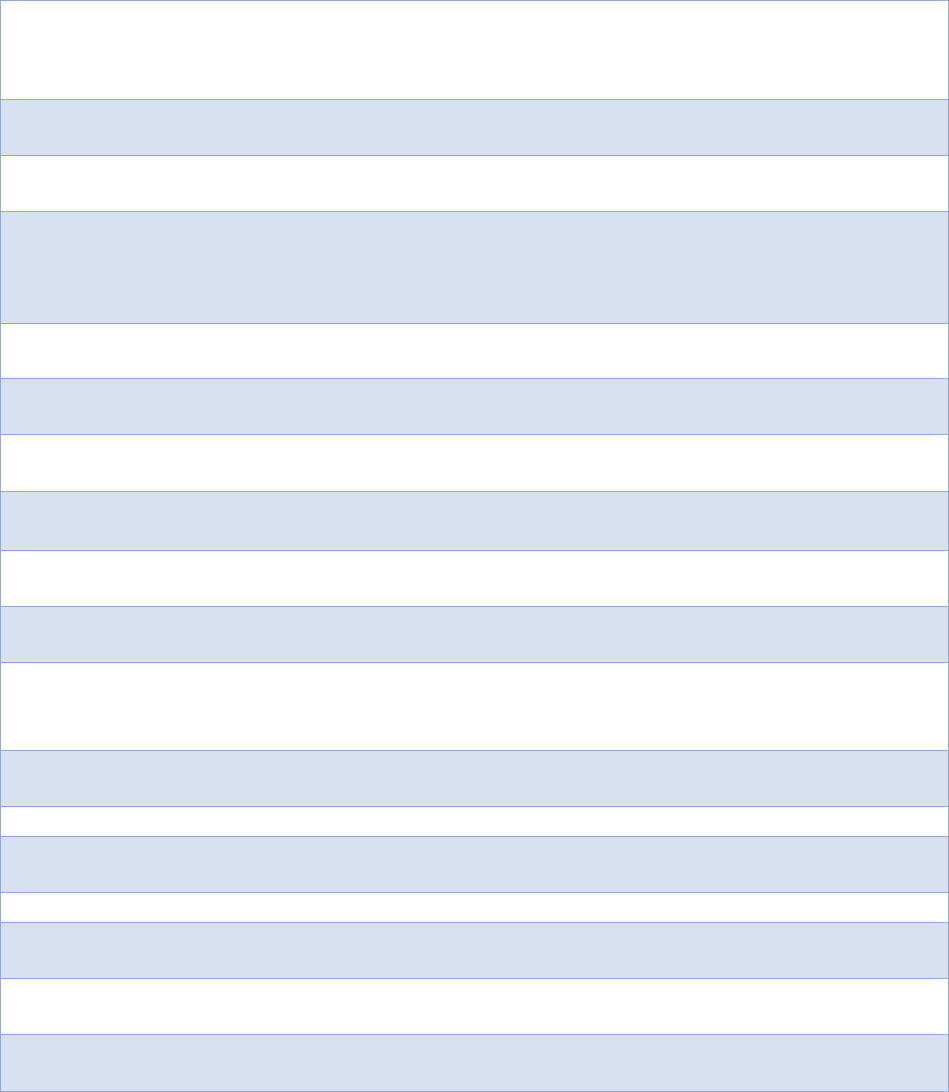

II. STATE ADOPTIONS

Currently, twenty-three jurisdictions have enacted the UCLA. The first jurisdiction to

adopt the UCLA was Utah, in 2010. Additional jurisdictions have adopted the UCLA

nearly every year since. The steady list of adoptions, including three in 2021, suggests

that the law is meeting the needs of the states. The chart below lists those adoptions (the

UCLA has been introduced for adoption in Missouri, West Virginia, Mississippi, and

Kentucky in 2023):

State

Adoption

Year

Form of

Adoption

Citation

Notes

Colorado

2021

Statute

Colo. Rev. Stat. §13-24- 101

Limited to family practice

New

Hampshire

2021

Statute

N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §

490-J:1

Virginia

2021

Statute

Va. Code Ann. § 20-168

Limited to family practice

North

Carolina

2020

Statute

N.C. Gen. Stat. § 1-641

Tennessee

2019

Rule

Tenn. Sup. Ct. R., Rule 53

Limited to family practice

703

6

Pennsylvania

2018

Statute

42 Pa. Cons. Stat. Ann.

§7401

Limited to family practice,

trusts and estate practice,

and matters arising under

corporate law

Illinois

2017

Statute

Ill. Comp. Stat. 90/5

Limited to family practice

New Mexico

2017

Rule

N.M.R.A., Rule 1-128.12

Limited to family practice

Florida

2016

Statute

and Rules

Fla. Stat. § 61.55; Florida

Fam. L. R. of Proc. 12.745; Fl.

B. R. Prof’l Conduct 4- 1.19

Limited to family practice

North Dakota

2016

Rule

N.D. Rule of Ct. 8.10

Limited to family practice

Arizona

2015

Rule

Ariz. R. Fam. L. Proc., Rule

67.1

Limited to family practice

Montana

2015

Statute

Mont. Code. Ann. § 25-40- 101

Maryland

2014

Statute

Md. Code Ann., Cts. & Jud.

Proc. § 3-2001

Michigan

2014

Statute

Mich. Comp. Laws § 691.1331

Limited to family practice

New Jersey

2014

Statute

N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2A:23D-1

Limited to family practice

Alabama

2013

Statute

and Rules

Ala. Code § 6-6-26 & Ala.

Rules of Priv. in Collaborative

Practice

Limited to family practice

Ohio

2013

Statute

Ohio Rev. Code § 3105.41

Limited to family practice

Washington

2013

Statute

Wash. Stat. § 7.77.101

District of

Columbia

2012

Statute

D.C. Code § 16-4001

Limited to family practice

Hawaii

2012

Statute

Haw. Rev. Stat. § 658G-1

Nevada

2011

Statute

Nev. Rev. Stat. Ann § 38.400

Texas

2011

Statute

Tex. Family Code Ann. §

15.052

Limited to family practice

Utah

2010

Statute

Utah Code Ann. § 78B-19- 101

Based on the adoptions to date, seventeen jurisdictions adopted the UCLA as a statute

via its legislature, four adopted the law as court rules, and two jurisdictions opted for

a hybrid approach. The drafters were aware that some jurisdictions would view the law

as one regulating attorney conduct and, thus, be adopted as a rule, while other

jurisdictions would view the rule as primarily involving privilege, and thus be best

adopted as a statute. Those options remain open to the adopting jurisdictions.

703

7

Some jurisdictions declined to enact the UCLA because they have legislation or court

rules pre-dating the Act. Lawyers in Minnesota were the first to use collaborative law,

and Minnesota has a court rule permitting the practice dating back to 1999.

5

California

has had a collaborative statute since 2006, but it only states that parties can agree in

writing to use the collaborative process to resolve any matter governed by the

applicable statues in California and it very briefly defines the collaborative process.

6

North Carolina adopted collaborative law statutes that are limited to family matters, but

in 2020, that state formally adopted the UCLA to apply to non-family matters.

Many states that have not yet adopted the Act still have robust collaborative law

practices, both in family and civil collaborative matters. New York, Massachusetts, and

California, for instance, have not adopted Act, but these states all have vibrant

collaborative practice groups. In 2009, the Boston Law Collaborative received the

prestigious “Lawyer as Problem Solver” award from the American Bar Association

Section of Dispute Resolution.

III. ETHICS

Collaborative law is an ethical form of limited scope representation, and the UCLA’s

provisions ensure conformity to best practices. The UCLA sets forth minimum

requirements for a participation agreement,

7

allows for a tribunal to issue emergency

orders in appropriate cases,

8

provides additional protections for low-income parties,

9

requires collaborative attorneys to assess the appropriateness of collaborative law in

each case,

10

and requires collaborative attorneys to conduct case assessment for

coercive or violent relationships to reasonably ensure participant safety.

11

The UCLA does not affect any of the lawyer’s duties under the Rules of Professional

Conduct. Instead, the UCLA clarifies how some of those ethical rules relate specifically

to the collaborative practice, particularly as it relates to the boundaries of the limited

scope arrangement, the participation agreement, and post-withdrawal conflicts of

interest.

In 2007, the American Bar Association Standing Committee on Ethics and

Professional Responsibility issued Formal Opinion 07-447, in which the ABA stated

5

Minn. Ct. Rule 111 (2023).

6

Cal. Ann. Fam. Code §2013 (2023). In addition to this law, many local California courts have rules

governing the collaborative process.

7

UCLA Section/Rule 4.

8

UCLA Section/Rule 7.

9

UCLA Section/Rule 10 (allowing another lawyer within the firm to represent low-income clients in

litigation if certain terms are met).

10

UCLA Section/Rule 14 (requiring informed consent on the part of the party).

11

UCLA Section/Rule 15 (requiring screening for abusive relationships and power and control

imbalances).

703

8

that collaborative law represents “a permissible limited scope representation.”

12

The

Opinion specifically rejected the notion that “collaborative law practice sets up a non-

waivable conflict” of interest.

13

In addition, between the years of 1997 and 2012, eleven

jurisdictions issued ethics opinions approving the collaborative process, so long as

certain conditions are met, such as ensuring informed consent (which is embedded in

the UCLA).

14

Colorado remains the only jurisdiction with an ethics opinion critical of

collaborative law as an impermissible conflict of interest; however, the opinion allows

collaborative law, provided that the lawyers do not sign the participation agreement.

15

In 2021, Colorado adopted the UCLA maintaining that lawyers are not permitted to

sign the participation agreement, but otherwise permissive of the practice.

16

The state ethics opinions largely arise from jurisdictions that subsequently enacted the

UCLA. Four additional jurisdictions (Minnesota, Kentucky, Missouri, and South

Carolina) also permit the practice of collaborative law by virtue of an ethics opinion. In

other words, twenty- seven jurisdictions explicitly permit collaborative practice under

state law, state ethical guidance, or both.

No jurisdictions have addressed the ethical questions regarding collaborative law in

more than a decade – thus there appears to be emerging consensus that the practice

is ethical, provided the lawyers meet their other ethical obligations under the Rules.

Similarly, the number of collaborative lawyers continues to increase. These facts

evidence the growing acceptance of collaborative law as a permitted, ethical practice.

IV. CONCLUSION

The lack of activity in the last decade regarding the concerns about collaborative point

to the dissipation of those issues. Almost half of the U.S. jurisdictions have adopted the

UCLA, and the Board of Governors should reconsider the Act and approve it.

12

ABA Formal Opn. 07-447, 3 (2007).

13

Id. (responding to the arguments set forth in a Colorado ethics opinion).

14

See N.D. Ethics Opn. 12-01 (2012) (permitting collaborative practice provided informed consent is

obtained); Ala. Bar Assoc. Opn. 2011-3 (2011) (same); S.C. Ethics Opn. 10-01 (2010) (collaborative

practice is permissible limited scope representation); Mo. Formal Ethics Opn. 124 (2008) (permitting

collaborative practice with informed consent by the clients); Wash. Ethics Opn. 2017 (2007)

(collaborative practice is permissible provided other elements of limited scope representation are

followed); N.J. Ethic Opn. 699 (2005) (permitting practice and providing pointers regarding informed

consent); Ky. Ethics Opn. E-425 (2005) (permitting the practice provided the lawyer still meets all other

ethical obligations); Md. Ethics Opn. 2004-23 (2004) (permitting a collaborative practice group); Pa. Bar

Ass’n Comm. On Legal Ethics and Prof’l Responsibility, Informal Opn. 2004-24 (2004) (finding the

collaborative practice is not a violation of the ethics rules); 2002 N.C. Ethi. Op. 1 (2002) (permitting

collaborative practice and collaborative practice groups); Minn. Advisory Opn. (Mar. 12, 1997)

(permitting collaborative practice if all other ethical obligations are met). All of these ethics opinions are

available on the website of the Global Collaborative Law Council, at

https://globalcollaborativelaw.com/ethics-opinions-on-collaborative-law/.

15

Colo. Formal Ethics Opn. 115 (2007) (Ethical Considerations in the Collaborative and Cooperative Law

Contexts).

16

Colo. Rev. Stat. § 13-24-104.

703

9

The work of the Drafting Committee is available in this archive:

https://www.uniformlaws.org/viewdocument/committee-archive-

2?CommunityKey=fdd1de2f-baea-42d3-bc16-a33d74438eaf&tab=librarydocuments

A direct link to the Uniform Collaborative Law Act and Rules is available here:

https://www.uniformlaws.org/viewdocument/final-act-101210?CommunityKey=fdd1de2f-

baea-42d3-bc16-a33d74438eaf&tab=librarydocuments

Respectfully submitted,

Lisa R. Jacobs, Executive Committee Chair

National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws

February 2024

703

10

GENERAL INFORMATION FORM

Submitting Entity: National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws

Submitted By: Lisa R. Jacobs, Executive Committee Chair

1. Summary of Resolution(s).

This Resolution approves the Uniform Collaborative Law Rules and Uniform Collaborative

Law Act, promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State

Laws (NCCUSL), as an appropriate Act and appropriate Rules for those states desiring

to adopt the specific substantive law suggested therein.

Although the UCLA may have been controversial when first presented to the House of

Governors in 2011, the last decade has demonstrated that collaborative law is a useful

and ethical practice for those who want to use it to solve disputes. To date, twenty-three

jurisdictions adopted the UCLA, and additional jurisdictions continue to introduce the law

for enactment or adoption by their legislatures or supreme court.

2. Indicate which of the ABA’s Four goals the resolution seeks to advance (1-Serve our

Members; 2-Improve our Profession; 3-Eliminate Bias and Enhance Diversity;

4-Advance the Rule of Law) and provide an explanation on how it accomplishes this.

The resolution would “Improve our Profession.” Collaborative law is a voluntary,

innovative, and contractually-based alternative dispute resolution process whereby

parties use collaborative attorneys to engage in negotiation to resolve their dispute and

refrain from any litigation activity during the course of the representation. This form of

dispute resolution has the promise of achieving a successful outcome and increasing

client satisfaction during a frequently challenging episode. The collaborative process

allows parties to work together to reach lasting solutions based on their respective goals.

Collaborative law is a voluntary process that appeals to many clients, particularly those

who have relationships that will continue into the future.

3. Approval by submitting entity.

NCCUSL granted final approval to this Act at its July 2010 Annual Meeting.

4. Has this or a similar resolution been submitted to the House or Board previously?

Yes. This resolution was previously submitted by NCCUSL in 2011, but it did not pass.

5. What existing Association policies are relevant to this Resolution and how would

they be affected by its adoption?

The ABA Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility issued Formal

703

11

Opinion 07-447 on “Ethical Considerations in Collaborative Law Practice.” This opinion

found that collaborative law does not run afoul of the Model Rules of Professional

Conduct. This resolution builds on – and does not contradict – Formal Opinion 07-447.

6. If this is a late report, what urgency exists which requires action at this meeting of

the House?

None.

7. Status of Legislation. (If applicable)

The Uniform Collaborative Law Act and Rules has been enacted in twenty-three

jurisdictions. It was introduced for enactment in Kentucky, West Virginia, and Missouri in

2023 and a petition to adopt the Uniform Collaborative Law Rules is currently pending

before the Mississippi Supreme Court.

8. Brief explanation regarding plans for implementation of the policy, if adopted by the

House of Delegates.

In addition to the twenty-three jurisdictions that have already implemented the policy,

NCCUSL will present the Act and Rules to the states for consideration and enactment.

9. Cost to the Association. (Both direct and indirect costs)

None.

10. Disclosure of Interest. (If applicable)

None.

11. Referrals.

Pursuant to the agreement between NCCUSL and the ABA, NCCUSL provides

information on all of its drafting projects to the ABA via the Section Officers Conference,

which notifies all ABA Special and Standing Committees, as well as Sections, Divisions,

and Forums. For all NCCUSL drafting projects, the ABA then appoints advisors who are

responsible for communication with other interested ABA entities during the drafting

process. Tentative drafts are provided upon request and are available on NCCUSL’s

website.

The Drafting Committee’s work can be found here:

https://www.uniformlaws.org/viewdocument/committee-archive-

2?CommunityKey=fdd1de2f-baea-42d3-bc16-a33d74438eaf&tab=librarydocuments

In addition, the Dispute Resolution Section referred this Resolution and Report to all ABA

Sections and entities this fall.

703

12

12. Name and Contact Information. (Prior to the Meeting. Please include name,

telephone number and e-mail address). Be aware that this information will be

available to anyone who views the House of Delegates agenda online.

Tim Schnabel, NCCUSL Executive Director

(312) 450-6604 (office)

13. Name and Contact Information. (Who will present the Resolution with Report to the

House?) Please include best contact information to use when on-site at the meeting.

Be aware that this information will be available to anyone who views the House of

Delegates agenda online.

Lisa R. Jacobs, NCCUSL Chair of Executive Committee

(215) 694-9996

703

13

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. Summary of the Resolution

This resolution approves the Uniform Collaborative Law Rules and Uniform Collaborative

Law Act, promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State

Laws (NCCUSL), as an appropriate Act and appropriate Rules for those states desiring

to adopt the specific substantive law suggested therein.

Although the UCLA may have been controversial when first presented to the House of

Governors in 2011, the last decade has demonstrated that collaborative law is a useful

and ethical practice for those who want to use it to solve disputes. To date, twenty-three

jurisdictions adopted the UCLA, and additional jurisdictions continue to introduce the law

to their legislatures or supreme court.

2. Summary of the Issue that the Resolution Addresses

When lawyers first began practicing collaborative law in the 1990s, questions arose

regarding the ethics of the process. In particular, critics questioned why the practice must

be structured as a limited scope representation, limited to negotiation efforts. Some of

these concerns led to the defeat of this resolution in 2011. Although every jurisdiction

passing on the ethics of collaborative law has found the practice to be ethical (with the

caveat that Colorado places some additional requirements on its collaborative lawyers),

some stigma remains.

The tide of acceptance for collaborative practice has turned, and just under half of U.S.

jurisdictions have passed a version of the UCLA. If passed, this resolution would provide

further support to the practitioners of collaborative law in their peace-making endeavors.

3. Please Explain How the Proposed Policy Position will address the issue

The proposed policy position would provide additional support for collaborative law,

particularly for those jurisdictions looking to enact their own version of the UCLA. The

policy position would support current collaborative practitioners, particularly those in

states who have not yet adopted the UCLA.

4. Summary of Minority Views or Opposition Internal and/or External to the

ABA Which Have Been Identified

In 2011, the resolution on the UCLA brought by the National Conference of

Commissioners on Uniform State Laws did not receive approval of the House of

Delegates. The Section of Dispute Resolution is currently unaware of any minority views

or opposition, and the Section believes that the developments in collaborative over the

last decade answer any questions previously raised.