Scientific, ethical, and legal considerations for the

inclusion of pregnant people in clinical trials

Catherine A. Sewell, MD, MPH; Sarah M. Sheehan, MPA; Mira S. Gill, BA; Leslie Meltzer Henry, JD, PhD;

Christina Bucci-Rechtweg, MD; Cynthia Gyamfi-Bannerman, MD, MSc; Anne D. Lyerly, MD; Leslie C. Mc Kinney, PhD;

Kimberly P. Hatfield, PhD; Gerri R. Baer, MD; Leyla Sahin, MD; Christine P. Nguyen, MD

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has under-

scored the ethical and health care de-

livery implications of the failure to enroll

pregnant people in clinical trials, and has

accentuated the already evident need for

efficacy and safety data to inform the use

of critical medical products during

pregnancy.

1

The data necessary to sup-

port the emergency use authorization of

COVID-19 prevention and treatment

measures for the adult population were

accrued with unprecedented speed,

outpacing the availability of clinical data

to supp ort timely enrollment of preg-

nant people in trials, and leading to

conflicting recommendations about

COVID-19 vaccine use in pregnancy.

2,3

Despite early studies indicating that

pregnant people are at higher risk of

developing complications owing to

COVID-19, and despite recommenda-

tions from the US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) COVID-19

guidance

4,5

and other organizations

and experts for the inclusion of pregnant

Click Video under article title in Contents at

From the Division ofUrology, Obstetricsand Gynecology, United StatesFoodand Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD (Dr Sewell); Duke-Margolis Center for

Health Policy, Washington, DC (Mses Sheehan and Gill); University of Maryland Carey School of Law and Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics,

Baltimore, MD (Dr Henry); Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ (Dr Bucci-Rechtweg); Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology &

Reproductive Sciences, University of California San Diego School of Medicine, San Diego, CA (Dr Gyamfi-Bannerman); Department of Social Medicine and

Center for Bioethics, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC (Dr Lyerly); Division of Pharmacology Toxicology for Rare Diseases, Pediatrics,

Urology and Reproductive Medicine, United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD (Drs McKinney and Hatfield); Office of Pediatric

Therapeutics,United States Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD (Dr Baer);Division of Pediatricand Maternal Health, United States FoodandDrug

Administration, Silver Spring, MD (Dr Sahin); and Office of Rare Diseases, Pediatrics, Urology and Reproductive Medicine, United States Food and Drug

Administration, Silver Spring, MD (Dr Nguyen).

Received Dec. 10, 2021; revised June 17, 2022; accepted July 14, 2022.

The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of or reflecting the

position of their respective institutions, member organizations, employing companies, health agencies, or one of its committees or working parties.

C.G.B. participated in paid lectures for Medela on breastfeeding and COVID-19 and for Hologic on late preterm pregnancy. The remaining authors report

no conflict of interest.

This publication was supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a

financial assistance award U19FD006602, totaling $873,663, with 100% funded by FDA and HHS. The contents are those of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by FDA, HHS, or the US Government.

0002-9378/$36.00 ª 2022 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.037

Clinical trials to address the COVID-19 public health emergency have broadly excluded

pregnant people from participation, illustrating a long-standing trend of clinical trial exclusion

that has led to a clear knowledge gap and unmet need in the treatment and prevention of

medical conditions experienced during pregnancy and of pregnancy-related conditions. Drugs

(includes products such as drugs, biologics, biosimilars and vaccines) approved for a certain

medical condition in adults are also approved for use in pregnant adults with the same medical

condition, unless contraindicated for use in pregnancy. However, there are limited pregnancy-

specific data on risks and benefits of drugs in pregnant people, despite their approval for all

adults. The United States Food and Drug Administrationeapproved medical products are used

widely by pregnant people, 90% of whom take at least 1 medication during the course of their

pregnancy despite there being sparse data from clinical trials on these products in pregnancy.

This overall lack of clinical data precludes informed decision-making, causing clinicians and

pregnant patients to have to decide whether to pursue treatment without an adequate un-

derstanding of potential effects. Although some United States Food and Drug Administration

initiatives and other federal efforts have helped to promote the inclusion of pregnant people in

clinical research, broader collaboration and reforms are needed to address challenges related

to the design and conduct of trials that enroll pregnant people, and to forge a culture of

widespread inclusion of pregnant people in clinical research. This article summarizes the

scientific, ethical, and legal considerations governing research conducted during pregnancy, as

discussed during a recent subject matter expert convening held by the Duke-Margolis Center

for Health Policy and the United States Food and Drug Administration on this topic. This article

also recommends strategies for overcoming impediments to inclusion and trial conduct.

Key words: clinical trials, clinical trial conduct, fetal health, maternal health, research during

pregnancy, US Food and Drug Administration

DECEMBER 2022 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 805

Special Repor t ajog.org

people in clinical trials, COVID-19

medical product development did not

specifically focus on the particular con-

dition of pregnancy. The exclusion of

pregnant people in COVID-19 trials is

one example of their routine exclusion

from medical product trials more

broadly. In addition, there is little clinical

development of products for pregnancy-

related conditions. As a consequence of

these practices, both patients and their

providers often have sparse information,

if any, with which to assess the bene fits

and risks associated with medical prod-

uct use during pregnancy for both the

pregnant person and the developing

fetus. Limited or absent information can

lead to unsafe use of medical products or

refusal or reluctance to prescribe or

accept necessary treatment.

The COVID-19 medical product trials

illustrate a long-standing trend of

excluding pregnant people from clinical

trials for prescription and nonprescrip-

tion drug products and biologic prod-

ucts (including vaccines), which has led

to a clear knowledge gap and unmet need

for evidence to inform both pregnancy-

related conditions and medical condi-

tions existing in pregnancy. Approxi-

mately 90% of pregnant people take at

least 1 medication in pregnancy, and

70% of those who are pregnant take at

least 1 prescription medication.

6e8

Medical products that are approved for

adults are also approved for pregnant

populations because pregnant people are

adults, barring a contraindication for the

use of some products during pregnancy,

even if pregn ancy-specific data are lack-

ing. Dosing studies of medical products

for conditions that exist in pregnancy

often do not include pregnant people,

forcing clinicians to use their clinical

judgment to extrapolate appropriate

dosage for similar efficacy when pre-

scribing treatments in pregnancy,

potentially leading to ineffective treat-

ment or excess toxicity. This knowledge

gap, and the potential adverse impact on

patient care, underscores the importance

of planning for the collection of data

needed to support use in pregnancy at

the beginning of product development

programs. To address the knowledge

gap, it is critical that studies necessary to

support enrolling pregnant people in

clinical tr ials, including nonclinical

developmental and reproductive toxicity

studies and clinical pharmacology

studies, are conducted as early as

possible.

The overall lack of clinical data in

pregnancy presents important chal-

lenges that regulators and clinicians are

actively seeking to address. To guide and

manage the use of medical products in

pregnant populations, regulatory

decision-makers and clinicians must

often rely on safety data from nonclinical

studies and efficacy and safety studies in

the nonpregnant populati on. Even if

data in pregnant people are eventually

collected in the postapproval setting, this

accrual often occurs slowly; hence, the

evidence gap persists for an extended

period of time after product approval.

Furthermore, data collected in the

postapproval setting in pregnant people

are often subjected to inherent biases

and confounders that may not be

adequately mitigated.

To address this knowledge gap and

encourage timely evidence generation

for pregnant populations, federal

agencies, patient organizations, and

collaborative publiceprivate partner-

ships have actively raised awareness of

key issues and are taking steps to boost

inclusion of pregnant people in clinical

trials (Table).

Although these initiatives have helped

promote the inclusion of pregnant peo-

ple in clinical research, broader collab-

oration and reforms are needed to

address challenges related to the design

and conduct of trials that enroll pregnant

people and to forge a culture of wide-

spread inclusion of pregnant people in

research.

Accordingly, the Duke-Margolis

Center for Health Policy, under a coop-

erative agreement with the FDA,

convened a public meeting in February

2021 to discuss the scientific and ethical

considerations for including pregnant

people in clinical trials. Meeting partic-

ipants represented a wide variety of

stakeholder categories including

academia, industry, governmental

agencies, and patient advocacy groups.

Below, we summarize key input from

meeting participants about the scientific,

ethical, and legal considerations gov-

erning research for pregnancy, and pro-

vide their recommendations on

approaches to overcome impediments to

including and conducting trials in preg-

nant people.

Scientific considerations

Nonclinical and clinical data are essential

components of drug development, and

both are critical for regulatory and clin-

ical decision-making for all patient

populations. The scientific consider-

ations and associated challenges dis-

cussed during the me eting fall into the

following categories:

1. Nonclinical studi es to support the

conduct of clinical trials in pregnant

people

2. Clinical data collection to support

regulatory decision-making and

evidence-based care delivery

Nonclinical studies to support trial

conduct

Nonclinical studies provide key safety

information that informs clinical trial

eligibility criteria, dosing decisions, and

drug labeling. Generally, nonclinical

studies to support enrolling pregnant

people in clinical trials include nonclin-

ical safety assessments from reproduc-

tive and developmental toxicity studies

in animals. At the meeting, representa-

tives from the FDA described the char-

acteristics of standard nonclinical

studies and their utility and limitations.

Detailed information regarding general

and specific nonclinical study conduct

and design can be found in a multitude

of published guidances by FDA, and in

conjunction with worldwide regulatory

agencies through the International

Council for Harmonisation of Technical

Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for

Human Use (ICH). Two pertinent re-

sources for this topic are ICH M3 (R2)

Nonclinical Safety Studies for the

Conduct of Human Clinical Trials and

Marketing Authorization for Pharma-

ceuticals, and ICH S5 (R3) Detection of

Reproductive and Developmental

Toxicity for Human Pharmaceuticals.

9,10

Special Report ajog.org

806 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology DECEMBER 2022

Meeting participants primarily dis-

cussed the characteristics and re-

quirements of 2 types of noncli nical

studies: reproductive toxicity and devel-

opmental toxicity studies. Reproductive

toxicity studies assess how drugs may

affect the reproductive competence of

sexually mature males and females.

Developmental toxicity studies assess

possible adverse effects from drug

exposure from preconception, prenatal,

or postnatal exposure on the developing

fetus up to sexual maturity. These

nonclinical studies use animal models

(typically rats and rabbits) that allow

safety assessment across gestational

stages, can be completed efficiently, and

are intended to inform safe use of med-

ical products throughout pregnancy.

These nonclinical animal models are

well established and accepted worldwide

for drug registration, have significant

background control data, have targeted

treatment periods with specific end-

points, and are intended to interrogate

high doses of drug molecules.

In general, pregnancy-related info r-

mation in the drug label to inform pre-

scribing decisions in the pregnant

person consists solely of evidence from

nonclinical studies at the time of dru g

approval. Although nonclinical studies

provide essential information, they also

have limitations. First, although rats and

rabbits serve as effective animal models,

the inherent species differences between

these animals and humans can lead to

some uncertainties when extrapolating

from animals to humans. For example,

some studies in animals may produce

safety signals at high doses that would

not appear in humans because of species

and related dosage differences, and thus

may provide some assurance for human

safety. Conversely, animal studies may

not capture harms that may occur in

human pregnancies. In addition, there

are study design limitations that affect

the translational utility of available ani-

mal models. For example, nonclinical

reproductive and developmental studies

are designed to capture only gross

morphologic and easily observable

functional effects of a drug. Thus, stan-

dard study designs do not include as-

sessments of drug effects on higher-

order learning and memory, immune

system development, endocrine system

functioning following puberty, or ani-

mal fetal exposure levels; although

specially designed studies can capture

these data if there is a known concern

that warrants these special studies.

Although nonclinical studies have

limitations, they are a vital component to

informing clinical research in pregnant

populations and must be completed

before progression to later stages of

clinical trials that enroll pregnant people.

Thus, the timing of reproductive and

developmental studies in the drug

development program is critical when

planning for trials enrolling pregnant

people. Although it would seem ideal to

perform these nonclinical studies early

to inform risk, doing so befo re knowing

the doses to be investigated in a

nonpregnant population in a clinical

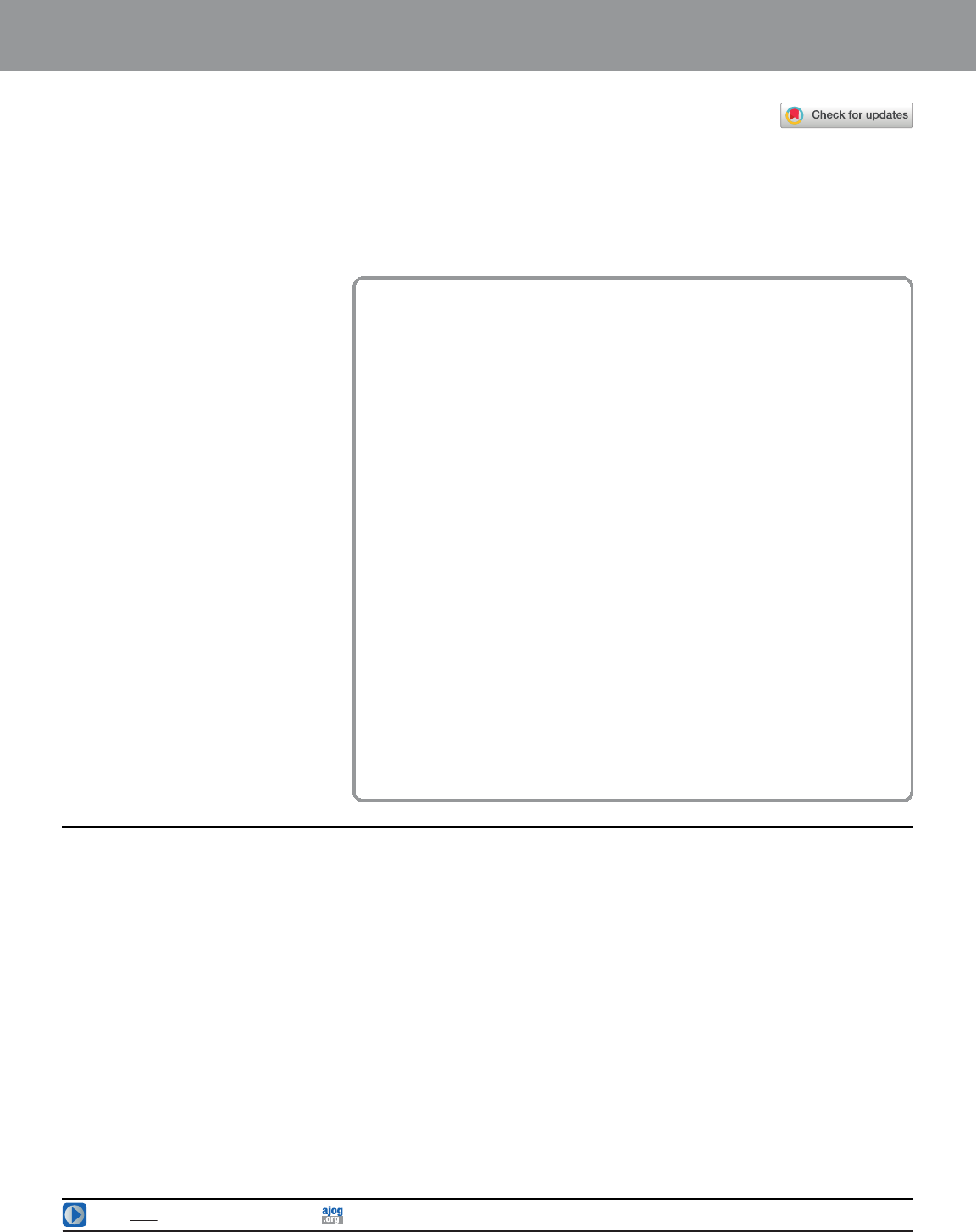

TABLE

Federal efforts to advance therapeutic research in pregnancy

FDA initiatives

FDA Office of Women’s Health

18

:

Advises the FDA Commissioner on

topics related to women’s health

Provides funding for research related

to women’s health

Maintains a pregnancy registry webpage,

supports workshops, and develops educa-

tional resources for pregnant people

FDA Perinatal Health Center of Excellence

19

:

Collaborates with other

FDA centers and external organizations to

support research to advance regulatory

science for perinatal populations

FDA draft guidance:

Pregnant Women: Scientific and Ethical

Considerations for Inclusion in Clinical Trials

Postapproval Pregnancy Safety Studies

National Institutes of Health initiatives

PregSource

20

:

Collects information from pregnant

people about pregnancy and overall

maternal health

Maternal and Pediatric Precision in

Therapeutics (MPRINT) Hub

21

:

Collects tools and

data to further maternal and pediatric

therapeutic development

Pregnancy and HIV/AIDS: Seeking Equitable

Study (PHASES)

22

:

Developing guidance for conduct of clinical

trials for HIV in pregnancy

PRGLAC

PRGLAC Report to the HHS Secretary and

Congress, September 2018

7

:

Describes knowledge gaps and ethical

considerations related to research in

pregnant and lactating people

Includes the Task Force’s 15 recommenda-

tions to improve therapeutic development for

pregnant and lactating people

PRGLAC Report Implementation Plan to HHS

Secretary, August 2020

23

:

Outlines implementation plan for the Task

Force’s 15 recommendations

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HHS, United States Department of Health and Human Services; PRGLAC, Task Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women and Lactating Women.

Sewell. Inclusion of pregnant people in clinical trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022.

ajog.org Specia l Report

DECEMBER 2022 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 807

trial can increase overall cost, prolong

data collection timelines for the general

drug development program, and may

delay therapeutic availability to the

general population. For most drugs

intended for the general population,

fertility and early embryonic develop-

ment (FEED) and embryofetal develop-

ment (EFD) studies are not conducted

until after or concurrently with Phase 2

studies, whereas pre- and postnatal

development (PPND) studies are often

concurrent or prior to Phase 3. For drugs

expected to be used by people who may

need treatment in pregnancy, con-

ducting these nonclinical studies early in

drug development to specifically ident ify

any pregnancy-related risks would allow

earlier inclusion of pregnant people in

clinical trials and facilitate the timely

collection of pregnancy-specific human

data before product approval.

Clinical data collection for decision-

making

Physiological considerations

Clinical research during pregnancy is

critical for supporting safe and effec-

tive drug use because physiological

changes during pregnancy can affect

the pharmacokinetics (PK) of a drug

and thus the dosage needed to reach

the intended therapeutic effect

compared with nonpregnant pop-

ulations. Such physiological changes

include: doubling of blood volume,

fluctuations in levels of circulating

binding proteins, slower gastrointes-

tinal transit time, and alterations in

me tabolism a nd excretion. Each of

these changes can var y over the dura-

tion of the pregnancy, thus it is

important to study therapeutic effect

and dosing throughout gestation.

Numerous patient characteristics and

medical conditions may coexist with

pregnancy, such as diabetes mellitus,

hypertension, chronic kidney disease,

and liver disease that can affect drug

metabolism, further underscoring the

need for robust PK studies in pregnant

people to guide safe and effective dosing.

In addition, fetal and placental develop-

ment can affect dispo sition of thera-

peutics during pregnancy because

different gestational stages are associated

with different susceptibilities and fetal

and placental physiological changes.

Absent knowledge of PK in pregnancy,

the appropriate modifications in dosing

to match physiological changes are un-

known and may result in either under-

dosing and inadequate treatment, or

overdosing leading to toxicities.

Trial design consi derations

Clinical research considerations also

include those related to trial design and

conduct. Clinical trial design and

conduct are influenced by factors such as

the drug class, study objectives, disease

area, and therapeutic context. Thera-

peutic context depends on various fac-

tors includ ing the nature of the disease,

whether there is an unmet medical need,

availability of treatments, and the po-

tential benefits and risks of a medical

product.

The objectives of clinical trials during

pregnancy can be divided into 2 broad

categories:

1. To support the development of ther-

apeutics for pregnancy-related con-

ditions (eg, preterm birth,

preeclampsia, intrahepatic chole-

stasis of pregnancy)

2. To support the development of ther-

apeutics for medical conditions that

coexist with pregnancy (eg, hyper-

tension, diabetes mellitus, COVID-

19)

In addition to clinical trial design,

there was extensive discussion at the

meeting about trial conduct and clinical

data collection considerations to allow

timely accrual of evidence for the use of

medical products in pregnancy. For

example, participants discussed a pro-

posed framework for conducting clinical

trials in pregnant people earlier in drug

development. Participants emphasized

that it was both possible and preferable

to begin evaluation in pregna nt people

during Phase 3 or earlier, as opposed to

conducting it solely in the postapproval

setting, with appropriate consideration

given to therapeutic context.

Participants noted there were major

operational barriers to pursuing some of

these approaches in both private- and

public-sector research. These barriers

are discussed in the legal considerations

section.

Ethical considerations

Meeting participants from all stake-

holder categories agreed that reticence to

include pregnant people in trials pre-

vents collection of data that inform as-

sessments of safety, efficacy, and

therapeutic dosage, thereby precluding

adequate information for informed

decision-making in pregnancy. Howev-

er, several participants noted that bar-

riers to enrolling pregnant people in

clinical trials persist largely because of

ethical concerns and outdated or mis-

informed ideas about clinical research.

A meeting participant specializing in

bioethics stated that clinical research in

pregnant people has been guided by a

protectionist ethic, which has ultimately

had harmful consequences. The protec-

tionist ethic has limited the autonomy of

pregnant persons, led to their exclusion

from research, and exposed them and

their children to harms of constrained

evidence. The protectionist ethic mani-

fests, for example, in a regulation guid-

ing clinical trials in pregnancy that

requires paternal consent, in addition to

maternal consent, when the prospect of

direct benefit applies only to the fetus.

This requirement fails to acknowledge

that the interests of a pregnant person

and their fetus are intertwined strands in

contrast to research conducted in pedi-

atric settings, where the consent of one

parent is sufficient to authorize research

with a prospect of direct benefittoa

child. In addition, participants under-

scored the importance of considering

altruism given that pregnant people may

choose to participate in research not only

when there is a direct benefit to study

participan ts but also when the research

could benefit other current and future

pregnant people.

Furthermore, researchers discussed

the ethical implications of requiring

contraception in certain trials where it

would not be needed or medically

acceptable to do so. Participants high-

lighted that requiring contraception in

cases where there is no prospect of

pregnancy (eg , a trial participant in a

Special Report ajog.org

808 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology DECEMBER 2022

same-sex relationship) raises ethic al

concerns by imposing unnecessary re-

quirements or preventing participation

in a study.

Ultimately, the meeting participant

emphasized the ethical principle of

protecting pregnant people, not from

research, but through research. In pre-

venting research in pregnant people, the

protectionist ethic does not in fact

eliminate or mitigate potential harm

from medical products. Rather, the po-

tential for harm remains unknown in a

clinical setting where prescribers and

patients must make decisions about

treatment, potentially exposing a larger

number of individuals to adverse events

than would occur in a trial setting.

Including pregnant people in clinical

trials provides the opportunity to assess

potential risks in a controlled setting, so

that risk mitigation strategies can be

identified to inform clinical care.

11

Finally, efforts to “protect” pregnant

people from research, which inevitably

lead to insufficient data, have led to the

reluctance to prescribe or accept neces-

sary treatment, putting pregnant people

in harm’s way from absent or under-

treatment.

Another meeti ng participant special-

izing in bioethics discussed 2 over-

arching ethical questions associated with

trial conduct and developing an ethical

framework. The first question was:

“When is it ethically permissible to allow

enrollment of pregnant people into

clinical research?” Participants noted

that researchers should first assess

whether there is preliminary evidence

during a drug development program

indicating potential safety signals. In

addition, researchers should decide

whether the development program in-

volves acceptable research-related risk.

This includes assessing the benefiterisk

ratio rather than just the poten tial risk.

Thus, it generally follows that the more

potential benefit offered through

participation in a given trial, the greater

the risk that might be acceptable to the

research participant.

The second question highlighted was:

“When do we have an ethical re-

sponsibility to enroll pregnant people in

a trial (eg, if it is permissible to enroll, do

we have a responsibility to enroll)?”

Participants noted that researchers

should consider the deg ree to which

obtaining adequate evidence for the use

of medication in pregnancy, or access to

prospect of benefit from trial participa-

tion raises concerns of justice, and if so,

whether exclusion of pregnant people is

appropriate.

Meeting participants emphasized that

the ethical framework governing

enrolling pregnant people in clinical

trials should be based on protecting

pregnant people through inclusion in

research. For example, participants

noted that institutional review boards

(IRBs), funder s, and other stakeholders

can elevate the ethical responsibility to

include pregnant people in research by

requesting justification for their exclu-

sion when pregnant people are excluded

from research. The development of a

framework or common criteria consid-

ered adequate justification for exclusion

could facilitate such efforts.

Legal considerations

In addition to ethical considerations,

participants discussed how legal con-

siderations, such as perceptions of lia-

bility, dissuade industry sponsors and

research institutions from enrolling

pregnant people in clinical trials. One

legal exper t highlighted 4 key legal con-

siderations that influence stakeholder

decision-making about whether to

include pregnant people in clinical trials.

First, the participant noted, there is a

myth that including pregnant people in

research is legally impermissible.

Although FDA guidance and federal

regulations set forth criteria for ethically

and legally conducting such

research,

12,13

some members of the

research enterprise mistakenly believe

that the law precludes research during

pregnancy.

14

That misperception of the

law can lead to decisions—by industry

sponsors, academic institutions, clinical

investigators, and others along the

research pathway—that exclude preg-

nant peop le from research.

15

Second, this myth is amplified by a

combination of absent and ambiguous

regulations. Current federal regulations

governing research during pregnancy

(commonly referred to as “Subpart B”

16

)

neither require the inclusion, nor

penalize the unjustified exclusion, of

pregnant people in research. In addition,

Subpart B contains ambiguities, such as

the concept of “minimal risk,” that are

open to w ide interpretation. In the face

of regulatory ambiguity, and without a

clear directive to include pregnant peo-

ple in research, stakeholders can apply

conservative regulatory interpretations

that limit the inclusion of pregnant

people in clinical trials.

Third, inclusion of pregnant people

in a clinical trial may increase trial and

overhead expenses (eg, expenses

related to liability cove rage). Inclusion

may also lead to slower trial recruit-

ment if a minimum sample of preg-

nant people is required, leading to

delays in trial completion and drug

approval. Exclusion, by contrast, not

only allows researchers to avoid those

costs and delays, but also mitigates

risks for industry by eliminating

premarket liability and shifting p ost-

market liability to prescribers and pa-

tients, who ultimately decide whether

to use medications w ithout pregnancy-

sp eci ficdata.

Fourth, although liability is

frequently cited as a reason that deci-

sion makers exclude pregnant people

from research, the legal expert high-

lighted that most stakeholders’ fears of

liability for harms to pregnant subjects

and their fetuses and offspr ing exceed

evidence of actual liability. Although

premarket testing is not risk-free, lia-

bility is limited to the size of the

research population and may be miti-

gated by obtaining fully informed con-

sent from each participant in research.

By contrast, legal risk might increase

substantially after a drug enters the

market if, for example, adverse events

occur in a patient population that was

excluded from clinical research.

Finally, the legal expert and other

panelists highlighted several key legal

strategies to advance inclusion of preg-

nant people in clinical trials. First, it is

imperative to determine the degree of,

and mitigate, liability stemming from

premarket clinical trials. Risk mitigation

strategies, such as implementing

ajog.org Specia l Report

DECEMBER 2022 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 809

programs that provide compensation for

research-related injuries, can dampen

disincentives to including pregnant

people in research.

17

Second, incentiv-

izing research during pregn ancy will also

promote inclusion of pregnant people in

clinical trials. For example, public

funding opportunities or accelerated

drug review could serve to incentivize

clinical research in pregnant pop-

ulations. All participants agreed that

concrete liability reforms and targeted

educational initiatives are necessary for

encouraging clinical research in preg-

nant people. Furthermore, to accom-

plish the goals listed above, clinical

research in pregnancy must be seen as a

critical public health issue, and legal ex-

perts, from both within and outside of

the research enterprise, should be

engaged to develop workable strategies.

Next steps

To ensure appropriate enrollment of

pregnant people in clinical trials, and

address evidence gaps that stem from lack

of enrollment, there must be a shift toward

creating a culture of inclusion of pregnant

people in clinical trials rather than

routinely excluding them without

adequate justification. As mentioned

above, the clinical research community can

aid in cultivating this, in part, by framing

the evidence gap as a critical public health

concern. Doing so would raise awar eness

for this crucial issue and illustrate the need

for collaborati on among various stake-

holders to affect widespread change.

In the absence of legislative authorities

for FDA, the research community and

government stakeholders can also begin

holding investigators accountable for

including pregnant people in research by

encouraging inclusion or requesting a

justification for their exclusion before a

trial receives IRB authorization. Support

for these measures is building. These

steps can be taken without new regula-

tions and guidelines because the existing

regulatory oversight infrastructure is

sufficient to support inclusion of preg-

nant people in clinical research.

Although creating a culture of inclu-

sion will take time, stakeholders can take

steps now to identify and address

priority evidence gaps and prioritize re-

sources on the basis of unmet need. For

example, researchers can begin by

studying medications that are already

being used in pregnan t people but for

which there are no objective data derived

from clinical research to support the

medication use in pregnant people. In

addition, the clinical research commu-

nity can encourage stakeholders to

develop criteria (eg, frequency of use,

seriousness of unmet medical need) for

identifying priority medications for

study in pregnancy and devote resources

accordingly. Researchers can leverage

existing data and trial infrastructure to

obtain evidence to facilitate regulatory

and clinical decision-making for drugs

already being used by pregnant people in

the postmarket setting.

Meeting participants from industry,

federal agencies, and academic

research institutions alike described

how existing data such as electronic

health records and registry data could

be leveraged to support evidence gen-

eration. In addition, data collection

through tr ial networks that have access

to more clinical sites and patients

couldsupportincreasedenrollment

and maximize data utility, whereas

alternative data sources can be used to

supplement clinical data collection for

regulatory submissi ons and clinical

decision-making.

Finally, increased collaboration

among stakeholders (federal agencies,

industry, academia, and patients and

patient advocates) involved in each

phase of drug development can sup-

port progress in a variety of ways. First,

stakeholder coop eration can encourage

liability reform and education. Second,

increasing collaboration can aid in the

implementation of innovative trial ap-

proaches, such as the development of

master protocols, to reduce time- and

cost-relat ed burdens and encourage

earlier enrollment of pregnant people

in drug development. Third, increasing

collaboration and communication with

the FDA to suppor t timely collection of

nonclinical data and discuss study

design can facilitate earlier enrollment

of pregnant people in clinical trials.

Finally, increasing both public and

private funding to suppor t nonclinical

and clinical data collection can fur ther

incentivize and support clinical

research in pregnancy.

-

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all the speakers and

panelists who participated in the Duke-Margolis

Center for Health Policy and US Food and Drug

Administration meeting entitled “Scientific and

Ethical Considerations for the Inclusion of

Pregnant Women in Clinical Trials” in

February, 2021.

REFERENCES

1. Modi N, Ayres-de-Campos D, Bancalari E,

et al. Equity in coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine

development and deployment. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2021;224:423–7.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gy-

necologists. Vaccination site recommendations

for pregnant individuals. 2021. Available at:

https://www.acog.org/covid-19/vaccination-

site-recommendations-pregnant-individuals.

Accessed October 25, 2021.

3. World Health Organization. The Pfizer Bio-

NTech (BNT162b2) COVID-19 vaccine: What

you need to know. 2021. Available at: https://

www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/

detail/who-can-take-the-pfizer-biontech-

covid-19– vaccine. Accessed October 25,

2021.

4. US Food and Drug Administration. Covid-19:

developing drugs and biological products for

treatment or prevention guidance for industry.

2021. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/

137926/download. Accessed October 25,

2021.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Develop-

ment of monoclonal antibody products targeting

SARS-CoV-2, including addressing the impact

of emerging variants, during the covid-19 public

health emergency guidance for industry. 2021.

Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/

146173/download. Accessed October 25,

2021.

6. Lyerly AD, Little MO, Faden R. The second

wave: toward responsible inclusion of pregnant

women in research. Int J Fem Approaches Bio-

eth 2008;1:5–22.

7. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of

Child Health and Human Development. Task

Force on Research Specific to Pregnant Women

Report to Secretary, Health and Human Ser-

vices Congress. 2018. Available at: https://

www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2018-09/

PRGLAC_Report.pdf. Accessed October 25,

2021.

8. Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM,

Kelley KE, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S. Medica-

tion use during pregnancy, with particular focus

Special Report ajog.org

810 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology DECEMBER 2022

on prescription drugs: 1976-2008. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 2011;205:51.e1–8.

9. US Food and Drug Administration and Inter-

national Council for Harmonization. M3(R2)

Nonclinical safety studies for the conduct of

human clinical trials and marketing authorization

for pharmaceuticals. 2010. Available at: https://

www.fda.gov/media/71542/download. Accessed

June 6, 2022.

10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration and In-

ternational Council for Harmonization. S5(R3)

Detection of reproductive and developmental

toxicity for human pharmaceuticals guidance for

industry. 2021. Available at: https://www.fda.

gov/media/148475/download. Accessed June

6, 2022.

11. The American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists. Ethical considerations for

including women as research participants.

2015. Available at: https://www.acog.org/

clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/

articles/2015/11/ethical-considerations-for-

including-women-as-research-participants.

Accessed June 16, 2022.

12. Food and Drug Administration. Draft guid-

ance, pregnant women: scientific and ethical

considerations for inclusion in clinical trials.

Federal Register. 2018. Available at: https://

www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-

04-09/pdf/2 018-07151.pdf. Accessed

August 4, 2021.

13. Department of Health and Human Services.

Additional protections for pregnant women,

human fetuses and neonates involved in

research. 2001. Available at: https://www.

govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2001-11-13/pdf/

01-28440.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2021.

14. Shields KE. Pregnancy and the Pharma-

ceutical Industry: The Movement Towards

Evidence-Based Pharmacotherapy for

Pregnant Women. London: Academic Press;

2019.

15. Mastroianni AC, Henry LM, Robinson D,

et al. Research with pregnant women: new in-

sights on legal decision-making. Hastings Cent

Rep 2017;47:38–45.

16. Office for Human Research Protections.

Additional protections for pregnant women,

human fetuses and neonates involved in

research. 2019. Available at: https://www.hhs.

gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/reg ulations/

45-cfr-46/common-rule-subpart-b/index.

html. Accessed October 25, 2021.

17. Henry LM, Larkin ME, Pike ER. Just

compensation: a no-fault proposal for research-

related injuries. J Law Biosci 2015;2:645–68.

18. US Food and Drug Administration. Office of

Women’s Health. 2019. Available at: https://

www.fda.gov/about-fda/office-commissioner/

office-womens-health. Accessed July 16, 2021.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. National

Center for Toxicological Research. Perinatal and

maternal research. 2021. Available at: https://

www.fda.gov/ab out-fda/nctr -researc h-focus-

areas/perinatal-and-maternal-research.

Accessed July 16, 2021.

20. National Institutes of Health. What is Pre-

gSource. 2021. Available at: https://pregsource.

nih.gov/. Accessed July 16, 2021.

21. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of

Child Health and Human Development. Maternal

and Pediatric Precision in Therapeutics

(MPRINT) Hub. 2022. Available at: https://www.

nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/opptb/

mprint#more. Accessed July 16, 2021.

22. US National Institutes of Health. PHASES:

pregnancy & HIV/AIDS: seeking equitable

study. 2016. Available at: http://www.

hivpregnancyethics.org/about-1. Accessed

October 25, 2021.

23. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute

of Child Health and Human Development.

Task force on research specific to pregnant

women and lactating women. Report Imple-

mentation Plan. 2020. Available at: https://

www.nichd.nih.gov/about/advisory/PRGLAC.

Accessed July 16, 2021.

ajog.org Specia l Report

DECEMBER 2022 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 811